THORNCOMBE’S FORGOTTEN 1644 EPIDEMIC

Epidemic: ‘Disease prevalent among (a) community at a special time’ (Oxford English Dictionary)

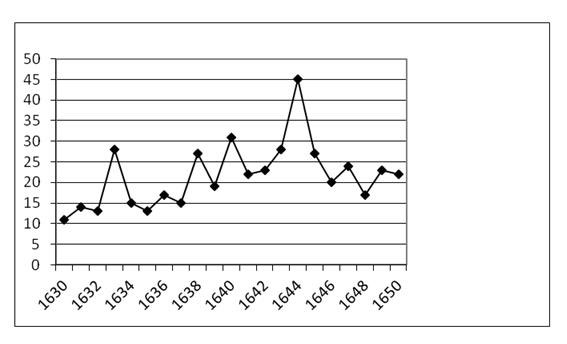

Between April and September 1644 Thorncombe suffered a mysterious rise in the number of deaths. Burials listed in the Parish Register increased to 46 compared with 28 in 1643 and 27 in 1645 at a time when rural populations tend to be stable. Alas no private letters, diaries or official documents survive to tell us exactly what happened. However, a possible explanation emerges when the circumstantial evidence is examined.

Figure 1: Thorncombe burials 1630-

17th century Thorncombe

Thorncombe parishioners today still cluster in the same parts of the parish as they did in the 17th century. Some houses were grouped around the church in Thorncombe village, and there were small communities living in the hamlets of Hewood and Holditch with the gentry living at Forde Abbey and Sadborow Hall. Others lived in isolated farms and houses scattered across the valley. However, while Thorncombe’s adult population is around 600 today, in the 17th century, Thorncombe’s population was approximately 900. Employment such as it was, came from domestic service, sheep farming, diary production, and the various processes involved in woollen cloth production, much of it done by piece workers.

Low Wages

Enclosure, the amalgamation of small pockets of land by landowners into larger holdings,

dates back to the Middle Ages. Property deeds and marriage settlements for Thorncombe

suggest that most of the land in Thorncombe was enclosed by 1644. England’s population

was on the increase. Healthy profits were to be made by farmers in the south-

But rural poverty resulting from enclosures and high food prices was a nationwide problem. In 1641 an official reported that ‘… the fourth part of the inhabitants of most of the parishes of England are miserable poor people, and (harvest time excepted) are without subsistence’. Unable to find grazing for their few animals or to grow crops for food due to enclosures, many of the rural poor were forced to seek work on the land as casual labourers. Supply exceeded demand. Wages were well below subsistence level. In 1654 Devon day labourers’ wages were increased for the first time since 1594 by 25% to 5s per week. Food prices rose by 50% over the same period.

Poor Harvests

To add to its problems, seventeenth century England was in the grip of The Mini Ice Age. Summers were times of flood and drought. Winters were freezing cold. Food and fuel were expensive and there was an economic recession as demand for consumer goods such as woollen cloth dropped. In 1644 the recorded price of wheat rose by 8%, which tells us that during the summer of 1644 while the sun shone, it was also very wet. Grain was in short supply, as yields were low. The price of spring sewn oats also increased in 1644 by 1%. So the winter of 1644 was dry and cold with spring frosts, which meant the ground was too hard to sow grain. The cold winters and the damp summers must have further undermined the health of Thorncombe’s population.

Siege of Lyme

In 1644 the port of Lyme was a key Parliamentarian garrison. Thorncombe was for Cromwell. An Easter Tuesday Fair took place each year. In 1644 it was held on 22 March. Disease was rife in the Parliamentarian and Royalist armies. It looks as though soldiers from the Lyme garrison visited the Easter Tuesday Fair and infected some of the locals with the same ‘sweating sickness’ which decimated Tiverton a few weeks later, as records of burials in Thorncombe start to climb in April and the pattern of deaths is identical to those recorded in Oxford the previous year.

On the 20 April the Royalists under the command of Prince Maurice, laid siege to Lyme. The siege lasted several weeks. The Earl of Essex’s Parliamentarian army set out from Blandford Forum, just over 40 miles away, on 15 June to relieve Lyme. Before Essex’s arrival Prince Maurice withdrew to Exeter. Essex then marched his troops through the Axe Valley to Tiverton via Taunton. An unnamed soldier was buried in Thorncombe on 27 June. Significantly an epidemic of ‘sweating sickness’ broke out in Tiverton following the arrival of Essex’s army.

Oxford Epidemic

Contemporary accounts of the Oxford epidemic describe how the symptoms of ‘the sweating sickness’ changed month by month. Fever and diarrhoea was followed by weakness and convulsions. During midsummer 1643, “the disease betrayed its malignant eruption of welks and spots”. By autumn the Oxford epidemic had nearly run its course. The symptoms were less severe and fewer died. With the onset of winter it vanished.

Thorncombe Epidemic

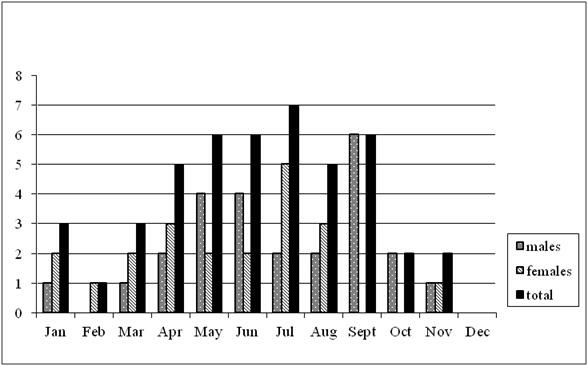

Mirroring the Oxford epidemic, burial numbers in Thorncombe continued to rise in May 1644 and tailed off from October onwards, with none taking place in December.

Figure 2: Thorncombe burials 1644

Although the cause of death is not given in Thorncombe’s Parish Register, circumstantial evidence suggests that Thorncombe’ 1644 mortality crisis, was brought to the village by Parliamentarian soldiers and like elsewhere in England, the already weakened populace quickly succumbed due to malnutrition and poor health resulting from a lethal combination of cold wet winters, unemployment, poor harvests, high food costs and civil war.

EVE HIGGS

August 2011

For a more detailed account including references and a bibliography see:

Higgs, E. (2009), Thorncombe’s 1644 mortality crisis, The Devon Historian, vol.

78, pp.15-

| History of the Trust |

| Constitution of the Trust |

| Minutes of meetings |

| Archived Minutes |

| Obituaries |

| Contacts |

| Newsletter |

| Newsletter Archives |

| Past Events |

| Blackdown Walk Aug 2013 |

| Bluebell Walk May 2013 |

| Pollinator Survey June 2013 |

| Visiting new-born lambs 2013 |

| 2014 Christmas Sale |

| Trees |

| Commemorative Trees |

| Johnson's Wood |

| Geology and geography |

| Wildlife |

| Birds |

| Chard Junction Nature Reserve |

| Nature Reserve pictures |

| Butterflies |

| Butterfly surveys |

| Photo albums |

| Artists and writers |

| Footpaths |

| General |

| Poor relief |

| Houses |

| In the news |

| Industry |

| Pubs |

| Religion |

| Reminiscences |

| Schools |

| 17th and 18th centuries |

| Harry Banks |

| Pissarro |

| Hedge Dating |

| Once upon a Thorncombe Road |

| Thorncombe's Lost Roads & Hidden Holways |

| Thorncombe's History |

| First World War Thorncombe men |

| Thorncombe's Changing Boundaries |

| Parish Poorhouse and Workhouses |

| The poor |

| Life in Thorncombe's Workhouse |

| Chard St Bakery & Forge |

| Holway Cottage |

| Forde Abbey |

| Gough's Barton |

| Holditch Court |

| Upperfold House |

| Sadborow Hall |

| Wayside |

| Thomas Place and The Terrace |

| Pinneys |

| 1 & 2 Church View Chard Street |

| Dodgy local ice-cream |

| Gribb arsenic poisoning |

| Industrial relics |

| Westford Mill |

| Thorncombe's Flax and Hemp Industries |

| Broomstick Weddings |

| Royal Oak |

| Golden House |

| St Mary's Church |

| Thorncombe's Chapels |

| Quakers |

| Commonwealth vicars |

| Who was William Bragge? |

| Holditch memories |

| St Mary's School |

| St Mary's School photos |

| Forgotten epidemic |

| Jacobites |

| Walk 1 |

| Walk 2 |

| Walk 3 |

| Walk 4 |

| Walk 5 |

| Walk 6 |

| Walk 7 |

| Walk 8 |

| A Village Walk. Walk 9 |

| Walk 10 |

| Rights of Way information |